Whenever I buy parts for a project, I always buy one or two extras. Over the years, I’ve amassed a sizable collection of random parts. Some of it will never be used, but sometimes my collection of parts has just what I need for something I want to build. I like when that happens.

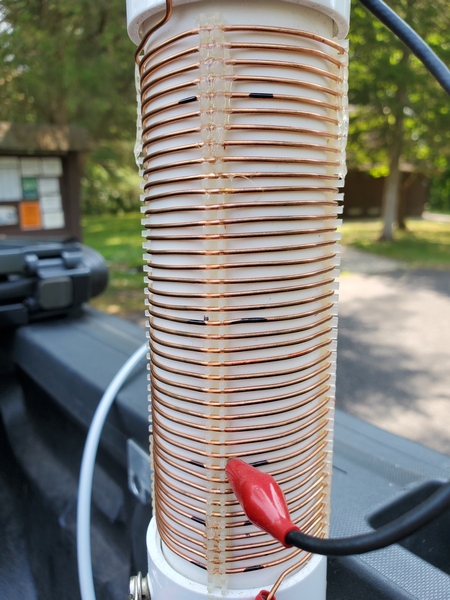

A while back I wrote about an old homebrew coil I resurrected and paired with a 12-foot telescopic antenna. The coil, while effective, was built to use with a much shorter whip and is larger than what I need. I scoured my junk box and came up with most of the parts I needed to build a scaled-down version.

I should note that I built this coil specifically to use with my old MFJ-1956 12-foot telescopic whip. In this configuration, this coil covers 40M through 17M. So, if you have a different whip or want to cover different bands, you’ll need to modify the design accordingly.

I used the old coil as a guide to determine the number of turns I needed to cover the bands of interest, adding two turns for good measure. Using an online shortened vertical calculator, I figured I would need about 13.4μH to load the 12-foot whip on the 40M band. Using an online coil inductance calculator, I estimated the total inductance of my coil to be 14.8μH. So, it covers 40M with a turn or two to spare.

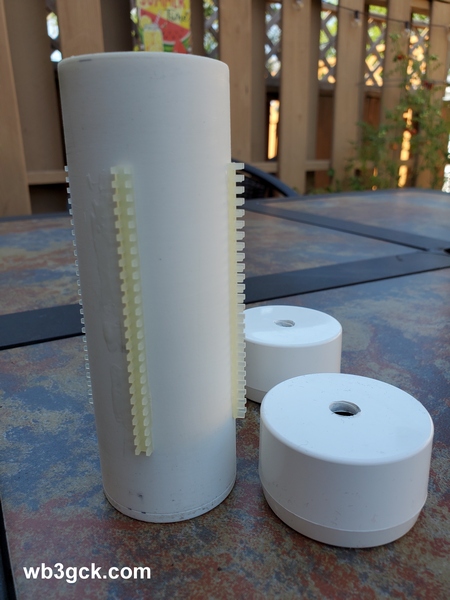

The new coil assembly measures 8.25 inches end-to-end, making it 2.25 inches shorter than the old coil. While it’s about 3.3 ounces lighter than the old coil, this new coil still weighs in at a hefty 10.8 ounces.

Parts List

With a few exceptions, my junk box provided the parts I needed to build the coil.

- 5-3/8 inches of 1.5 inch PVC pipe

- (2) PVC end caps for 1.5 inch PVC pipe

- (4) pieces of nylon grommet edging, 3.25 inches each. (The material I used has about 8 notches per inch)

- 16 gauge bare copper wire, approx. 12.5 feet

- (1) 3/8-24 coupling nut, 1-1/8 inches long

- (1) 3/8-24 x 1-1/4 inch stainless steel bolt (bottom mounting stud)

- (1) 3/8-24 x 1 inch stainless steel bolt (top bolt)

- 3/8 inch flat washers & lock washers

- (2) #10 x 3/4-inch self-tapping screws

- Approx. 6 inches of RG-174 coax

- Small alligator clip

- Misc: ring lugs for ⅜-inch & #10 screws

Construction Notes

As shown in the accompanying photo, I drilled the end caps to accommodate the ⅜-24 bolts. The 1-1/4 inch bolt was used for the bottom of the coil, along with a flat washer and a lock washer. The 1-inch bolt was used for the top, along with flat washer, lock washer, and the coupling nut.

The coupling nut was one item I didn’t have in my junk box. My local hardware store is well-stocked, but they didn’t have them with the ⅜-24 thread. I eventually found what I needed on Amazon. It was a little pricey, but I didn’t have any better options at the time.

After cutting the PVC pipe to length, I temporarily installed the end caps. Then, I cut four pieces of the grommet edging to length and glued them on, using Goop® adhesive. Unfortunately, I can’t provide a part number and source for the edging. A local QRPer, Ron Polityka WB3AAL (SK), gave me several pieces many years ago. I’m pretty sure Panduit was the manufacturer. My stash was nearly depleted, but I had enough left for this project.

Before assembling the end caps, I made two short jumpers, each with a ⅜-inch ring lug on one end, and a smaller ring lug on the other. Then I tightened everything up. I left about a ½ inch of thread on the top bolt to go into the coupling nut. I was careful to ensure that my whip antenna would fully thread into the coupling nut.

Before winding the bare wire on the coil form, I installed a ring lug on one end. I drilled a pilot hole in the side of the lower end cap and used a self-tapping screw as a connection point. When you wind the wire on the coil form, try to get the turns as tight as you can. (I didn’t do as good a job winding the coil as I would have liked.) Once I finished winding the coil, I cut the wire to length and installed a ring lug. I used some more Goop adhesive on the grommet edging to hold the turns in place.

The last step was to build the clip lead. For this, I used a piece of RG-174 coax. There’s nothing magical about the RG-174; stranded hookup wire would be fine. I used RG-174 primarily because of its flexibility, plus the shield would be a good RF conductor. (The center conductor was unused.) I crimped and soldered a ring lug to the braid on one end, and soldered an alligator clip to the braid on the other end. Then I used another self-tapping screw on the top end cap to connect everything together.

On the Air

I wrote about my initial tests of the coil in a previous post. Using an antenna analyzer, I determined where to place the tap for each of the four bands. I then used a permanent marker to mark these locations on the coil, so I can quickly change bands without resorting to the antenna analyzer.

With the antenna mounted on my truck, the SWR is higher than I would like on 40M and 30M. This is not unlike other shortened, base-loaded verticals I’ve used in this configuration. An additional counterpoise wire or two might help. Also, grounding the bottom of the coil and feeding it a couple turns up from the bottom would provide a precise match on the lower bands. I’ve used that technique in the past. That configuration , however, is a bit more complicated to implement, given the way I plan to use this coil. So, I just use a tuner to keep the radio happy, and the antenna seems to work fine.

Wrap-up

My older, larger coil worked fine; so technically, this project was unnecessary. But, since I had most of the parts on hand, what the heck. It was a fun project, and I’m sure it will see a lot of use in the future.

73, Craig WB3GCK